Upcoming data privacy regulations are preventing Meta’s new microblogging app “Threads” from launching in European Union (EU) markets. Experts say this is only the beginning of the privacy battle facing the Twitter clone.

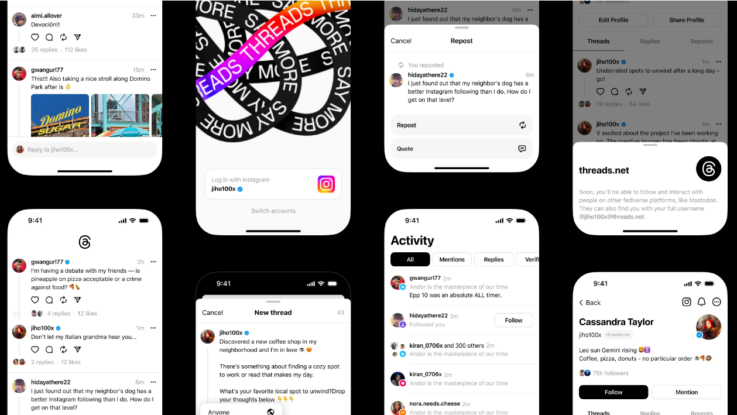

Meta’s attempted coup d’etat against the Twitter kingdom launched on Wednesday in over 100 countries, earning tens of millions of users in only its first day live. That, despite being unavailable to major markets within the EU.

The holdup has to do with “complexities with complying with some of the laws coming into effect next year,” Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri hinted on July 5. Mosseri’s statement may refer to the new antitrust-oriented Digital Markets Act, but experts also expect Threads to collide head-on with consumer privacy regulations, thanks to its wanton collection of just about every kind of personal data imaginable.

“It seems likely that they’re worried about the risk of rolling out something new that very clearly violates General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) guidelines,” says Aaron Mendes, CEO and co-founder of PrivacyHawk. But Threads’ slow rollout doesn’t preclude it from flourishing in the future. “Facebook has a reputation of rolling things out over time — they like to get stuff out fast, and then get information in and iterate.”

Everything Threads Will Know About You

Meta has a history of conflict with regulators, owing to its liberal approach to consumer privacy. The EU has already fined the media giant to the tune of nine figures or more on multiple occasions.

Judging by its entry in the Apple app store, it’s no wonder that Threads is being shielded from EU scrutiny. Browsing history, geolocations, health and financial information, and much more are all up for grabs. There’s even a dedicated category for “sensitive information” which, according to Apple’s documentation, includes “racial or ethnic data, sexual orientation, pregnancy or childbirth information, disability, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, political opinion, genetic information, or biometric data.”

According to Mendes, there’s no reason for users to suddenly freak out. For one thing, even the most egregious data collectors now provide settings for users to toggle what kinds of information they’re willing to divulge. And at the end of the day, he points out, “Threads is effectively Instagram. You use Instagram to log into it. So it’s all the same data collection, all the same protocols.”

Threads does distinguish itself from its parent platform in its supplemental privacy policy. One rule of particular note: It’ll only be possible to delete a Threads account by deleting the Instagram account associated with it.

Few of the tens of millions of people who’ve already signed up for Threads — or the hundreds of millions to come — are likely to know about this rule before it’s too late. It just goes to show how “the customers are very, very disempowered,” says Jim Killock, executive director of the Open Rights Group. “It’s worth remembering that people have invested thousands and thousands of hours into building their networks on these platforms. We wouldn’t tolerate this sort of behavior anywhere else.”

Can Meta Keep Up With GDPR?

Even those who hold no quarter for Meta’s approach to privacy may find certain GDPR regulations overly restrictive.

“EU laws make it very difficult to roll out a product, because of how they handle data sharing outside of EU borders,” Mendes says. In May, for example, Meta got handed a colossal 1.3 billion Euro fine for transferring EU citizens’ data to US servers, “which is kind of required to operate a service.”

Initially, the Privacy Shield program provided a framework for data transfer between the US and EU, but the European Court of Justice struck it down on July 16, 2020. A new Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Framework was agreed on in March, but hasn’t been enacted yet.

Even if the EU has good reason to want to maintain legal control over its citizens’ data, Mendes says, it’s unduly difficult for global brands to keep all their data in one place, “unless you create a copy of your product that’s completely siloed and works in the EU, separate from the one that you have, let’s say, in the United States, which is an engineering nightmare, because now you have to maintain two versions of your product.”

“There’s never a simple balance,” Killock admits. “It’s about respecting the desires of customers on one hand, and on the other hand ensuring that companies can do business.”

In some cases, he says, rules can help both regulators and users without being overly restrictive to companies. He points to the UK’s right to data portability law as a way to foster competition, and naturally discourage Meta’s more unsavory practices. “Whether we’re talking about moderation standards or privacy standards, it allows people escape routes, and that creates actual commercial pressure on these companies to behave better.”

“That,” he thinks, “will empower not just users but also regulators to say: ‘Look, people don’t like this practice, you shouldn’t be doing it.”