SAN FRANCISCO – Cybersecurity experts have long stayed in their problem-solving lane when it comes to finding vulnerabilities, patching bugs and keeping networks safe. But maybe it is time they applied their defensive skillsets and adversarial understanding of cyberthreats to help solve some of today’s most complex social issues.

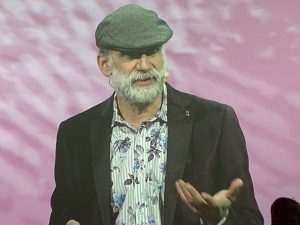

Speaking at the RSA Conference 2020 on Thursday, security technologist Bruce Schneier called for a better cooperation between security experts and government policymakers. The premise being, cybersecurity often requires nonlinear problem-solving, a quality conventional bureaucrats often lack.

From education systems to election structures, society is built on conventional “models” that made sense when they were first formed hundreds of years ago, said Schneier, a lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School. But these “good faith” models can’t keep up with constantly evolving threats and unanticipated societal changes.

[For Threatpost’s complete RSA Conference 2020 reporting, please visit our special coverage section, available here.]

Meanwhile, cybersecurity researchers spend their days looking for threats that could crop up in various products and software. Security experts need to be proactive in thinking about how attackers are constantly shifting their tactics, techniques and procedures and how those changes will impact security risks.

With that in mind, Schneier asked, “Can our expertise in IT security transfer to broader social systems, like tax code, like the system we use to choose our elected officials, like the market economy? Is our way of thinking in analytical frameworks valuable in a larger context? Can we hack society?”

Take, for instance, the complex federal tax code, which is made up of thousands of pages detailing rules for individuals and businesses to follow to determine what percentage of their incomes need to be forked over to the federal and state government. A “hacker mindset” could be helpful in looking at tax code and asking questions around who audits it, who pays for it, how the code can be patched, or how a security system could be designed to deal with discovered tax-related “vulnerabilities”.

“We’ve developed a unique skill set to understand technical systems with human dimensions, and to think about systems with an adversarial mindset,” said Schneier.

“We’ve developed a unique skill set to understand technical systems with human dimensions, and to think about systems with an adversarial mindset,” said Schneier.

The security space views a hack as something that a system allows, but that is unwanted by the system designers – and can lead to an exploitation of the system by an attacker. This definition of a “hack” can be also applied to society, where systems have been created for societal models that are constantly becoming outdated, based on changes in scale or circumstance, Schneier contended.

For instance, the legislative process is often so complex and difficult to understand, yet it allows for loopholes. Also, while conservative investment markets are based on knowledgeable buyers making decisions among competing products, a venture capitalist can end-run the “system” and fund (or “hack”) a startup, allowing it to take on risk in the hopes of quick success.

Schneier said the same cybersecurity-mindset can be applied to election security. It is also continually shifting, as the emergence of social media has created a ripple effect of disinformation that eventually has consequences on voting results.

When looking at how to solve these societal issues, policy makers need to ask themselves many of the same questions that security experts ask everyday. What are policy makers trying to protect? What are the risks? How well are the risks evaluated? What other risks do the solutions cause and what are the non-security trade offs?

“We need to upend the idea that society is stable,” said Schneier. “We built society and now we’re building it increasingly with technology.” Hacking society, in this context, is a natural extension of traditional problem solving.

This week at RSA, others have discussed the advantages of the security space branching its skillsets out to other industries.

A panel of experts discussing the legal policies available for machine learning attacks worried that a lack of laws swing open the door for bad guys to attack systems. Wendy Nather, head of advisory CISOs at Cisco, told a keynote audience that the security space needs to shift its relationship with other industries. “We have to open up our security culture to everybody,” she said on Tuesday. “Security needs to be basic knowledge and freely available. We can’t shoehorn people into our narrow society culture.”