Chinese advanced persistent threats (APTs) are known for being sophisticated, but the “ToddyCat” group is bucking the trend, compromising telecommunications organizations in Central and Southeast Asia using a constantly evolving arsenal of custom-developed, but very simple, backdoors and loaders.

ToddyCat was first discovered last year, though it has been in operation since at least 2020. According to Check Point, it has previously been linked with Chinese espionage operations.

In a blog post published this week, Check Point’s researchers described how the group is staying nimble these days: by deploying, and just as quickly throwing away, cheap malware it can use to drop its payloads.

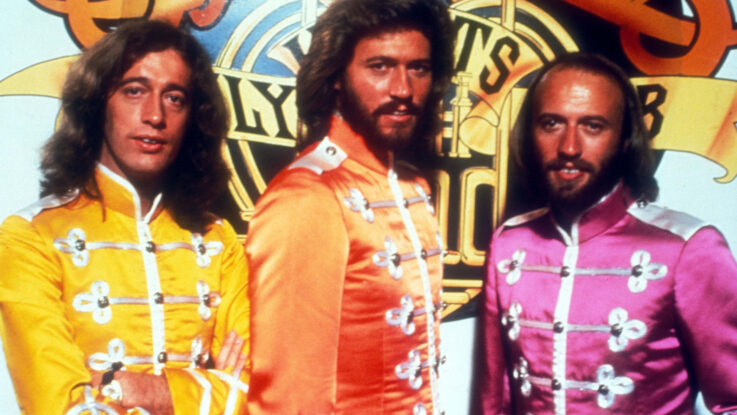

Victims of its latest “Stayin’ Alive” campaign — active since at least 2021 — include telcos from Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam. The precise extent of their reach, and whether they caused any damage, are yet unknown.

ToddyCat’s Latest Tactics

Stayin’ Alive attacks begin with spear phishing emails containing archive files. Once executed, the archive files are designed to take advantage of CVE-2022-23748, a 7.8 out of 10 “High” criticality DLL sideloading vulnerability in Dante AV systems software. ToddyCat uses such DLL sideloading — a popular technique, especially among Chinese threat actors — to drop loaders and downloaders onto targeted devices.

These loaders and downloaders are not nearly to the specs one would expect of a high-level, state-affiliated threat actor, explains Sergey Shykevich, threat intelligence group manager at Check Point.

“They have relatively basic functionality, but they’re good enough to achieve initial goals, like allowing the attacker to get basic reports about infected machines: computer name, user name, system info, some directories, and so on. They also include the functionality of shelling, allowing the execution of any command the attacker wants,” he explains.

“Our assumption is that via the shell, they were able to implement additional backdoors and modules,” he adds, though the research didn’t extend to finding out what payloads they ultimately did deploy.

A Smart Use of Dumb Malware

Though at first it might seem lazy or ineffectual, there is a reasoning behind using such basic tools instead of more sophisticated, multifunctional weapons of cyberwar.

“The smaller the tool, the more difficult it is to detect,” Shykevich explains. “And also, when it’s a small tool, it’s relatively easy to adjust it to a target.”

Easier to adjust, and less expensive to throw away. Typically, researchers identify and track APTs by cross-referencing details between different attacks. With ToddyCat, however, it’s impossible to do that — each of its malware samples has zero discernible overlap with known malware families, or even with one another. The researchers expect that they’re likely discarded for new samples even after little use. “The small changes mean that you can catch one of them, but it won’t be so straightforward to catch all the others. It will require some additional work,” Shykevich says.

That said, ToddyCat is undone by the fact that each sample traces back to its easily identifiable command-and-control (C2) infrastructure.

To defend against such a nimble attacker, Shykevich recommends a layered approach. “The first layer here, for example, was the email — you should have proper email protection to identify a malicious attachment,” he advocates. “But another level is endpoint detection and response (EDR) endpoints, to identify for example the DLL sideloading and malicious shell activity.”